11 October 2014: Heading from Hassan Abdal to Rawalpindi, I was looking forward to meeting Noori.

In 1996, Kaka, a 28-year-old Pakistani from Mansehra, had visited Delhi under Tablighi Jamaat, to impart an understanding of Islam at the Hazrat Nizamuddin Centre of learning. Kaka, a devout Muslim has dedicated his entire life to the service of Islam. Years before partition, his father Isher Singh, born a Sikh had willfully accepted Islam, renaming himself Gulam Sarwar. In Delhi, Kaka decided to try and re-connect with his relatives, who had migrated to India in 1947. Having no connection within the Sikh community in Delhi, Kaka remained at loss where to start. While walking on the streets, Kaka started randomly reaching out to Sikhs, asking if they knew anyone who may have migrated from Mansehra.

By sheer luck, a stranger provided him a clue that there is a family from Mansehra running a shop at Azad market. The next day, Kaka was there, meeting every Sikh shopkeeper. Finally, he met Tejpal Singh, my second cousin from paternal lineage, whose father had migrated from Mansehra. Tejpal being the same age as Kaka had heard stories about picturesque Mansehra and the holocaust of partition. He welcomed Kaka and took him home to meet his grandfather.

As Tejpal entered the courtyard of his house, he called out to his grandfather, “Bhapaji, look who is here.”

Kaka, trailing behind Tejpal was shocked to hear his grandfather say, “He looks like Isher!”

Kaka was a splitting image of Isher Singh aka Gulam Sarwar. In sheer delight of having connected to a distant relative, Kaka raised his hands to thank Allah for his graciousness.

Having spent memorable time connecting with more of his distant relatives in Delhi, when Kaka was departing for Pakistan, Tejpal’s father, Jaswant Singh told him with a heavy heart that his sister Jaswanti had been left behind in Pakistan. No one knew what had happened to her but he had a feeling that she may have survived.

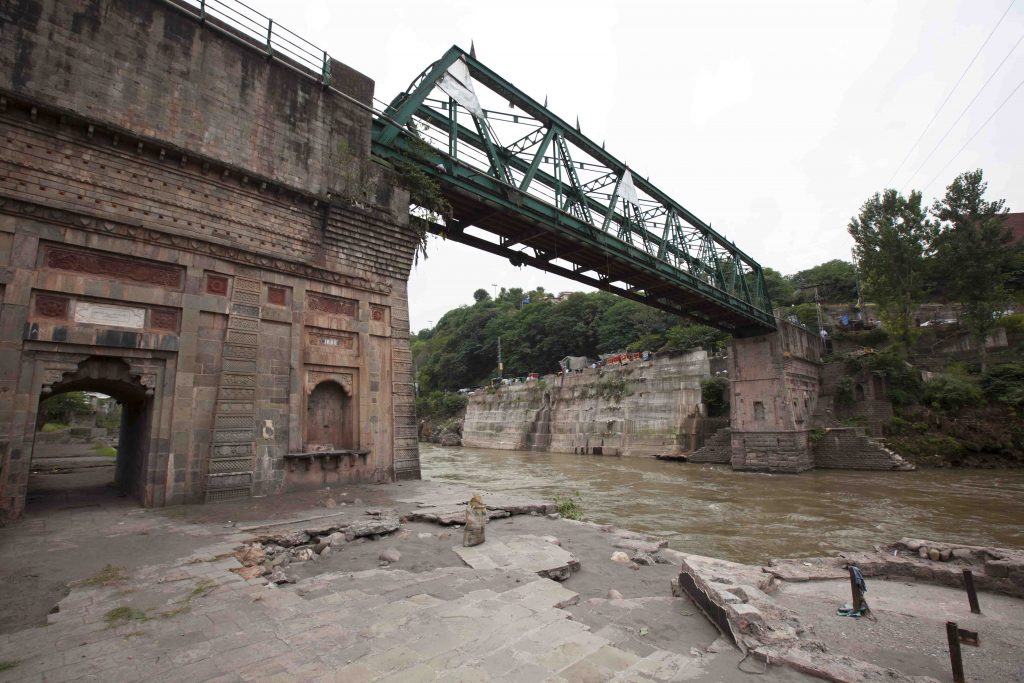

Jaswanti was five years old when tribals from Waziristan had attacked Muzaffarabad on 22 October 1947. Jaswanti’s parents, belonging to Mansehra, were at their second home at Muzaffarabad when tribals broke in. Seeing the violence inflicted on her parents, little Jaswanti ran out of the house in panic. A few hours later when she returned, there were blood stains all over the house. Looking for her parents, she headed out on the street, reaching the bridge on Jhelum River, where amongst many massacred corpses, she found the mutilated body of her mother.

She was standing alone in a complete state of shock when Mansood, a local Muslim approached and comforted her. Numbed and too stunned to react, she simply followed him. As they climbed the hill, Mansood read the Qalma, encouraging her to recite it with him, which was a subtle confirmation of the little girl having accepted Islam. She was later renamed Noori. She was married at the age of 13, bearing five children but soon her husband died of tuberculosis.

After her husband’s death, Noori decided to lead an independent life and moved to Abbotabad. With Sikhs having migrated, there was no biological family member to whom she could turn to. Dejected, having little choice but to live on to support her children, she continued to face challenges.

In the late 1970s, while visiting Mansehra, she noted a shop that she recalled having visited as a child with her father. She approached the owner, who happened to be Gulam Sarwar aka Isher Singh. She was overwhelmed with joy at meeting someone related to her biological parents.

On his return to Mansehra, Kaka was aware of Jaswant Singh’s mention of his sister Jaswanti having been left behind in Pakistan. Finding her would be like looking for a needle in a haystack. He had no clue as to where to begin the search.

Two years had passed since his trip to Delhi and one day his sister asked if it could be Noori, whom their father, Gulam Sarwar had once brought home to meet the family in late 1970s? For personal reasons, Noori had not maintained in contact with their family for years. However Kaka’s sister vaguely remembered her place in Abbotabad, where their father had once taken them.

Kaka now went in search of Noori, who by then had married a doctor and moved to Rawalpindi. Noori had three children from her second marriage. Getting Noori’s address from her neighbour at Abbotabad, Kaka was able to locate her in Rawalpindi. Re-establishing the connection, Kaka suggested to Noori that she should allow him to link her with Jaswant Singh in India, as there existed a possibility the two might well be siblings. Noori being a victim of fate, preferred not to reopen old wounds and politely refused!

Kaka, having experienced the affection of Tejpal’s family in Delhi, remained insistent. In search for Jaswanti for two years and nearly there, he did not want to give up so easily. He independently decided to sponsor Jaswant Singh’s visit to Pakistan.

In 1999, when Jaswant Singh arrived, Kaka asked him to stay at Panja Sahib Gurdwara, while he would try to again convince Noori. In an emotional plea, Kaka asked Noori to respect Jaswant’s feelings and meet him once as he had travelled all the way from India, just to meet her. Noori remained apprehensive but eventually yielded because of Kaka’s persistence.

A day later, they left for Panja Sahib Gurdwara. The moment had arrived when the potential siblings were to meet after half a century but the dilemma was that having been parted at a young age, how could the relationship be validated?

Strange indeed are God’s ways!

Just two months before the violence of October 1947 in Muzaffarabad, Jaswanti wanted her brother Jaswant to give her a ride on his new bicycle. As Jaswant cycled uphill, raising himself from the seat to push harder on the pedal, his foot slipped, jamming his right toe in the chain and severing it. That accident had remained imprinted in Jaswanti’s childhood memory.

When the two finally met at the gate of Panja Sahib Gurdwara, Jaswant Singh was bare foot. As Noori approached, her eyes fell on his feet. The missing right toe jolted her memory and reunited them finally.

Hereafter, Noori visited India many times to meet her family. Fondly she would be called Jaswanti in India while she remained Noori in Pakistan.

At the age of 80 years, Noori breathed her last on 16 June 2020 at Rawalpindi (Pakistan).

Noori, aka Jaswanti, born a Sikh, accepted the ‘Divine Will’ and lived her entire life as a devout Muslim! Noori is my distant Aunt, whom I last met at Rawalpindi in 2018. In this meeting, when I showed her the book, ‘LOST HERITAGE The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan’, which I had authored, she appeared disappointed that I did not show her picture in the chapter, ‘Meeting Noori’, which was dedicated to my first meeting with her in the year 2014. My reason was well-intended, to protect her privacy.

While expressing condolences over phone from Singapore to her son in Rawalpindi, when I shared my above interaction, he replied, “It is because of her Sikh blood that even as a devout Muslim, she remained fearless of her past being judged by anyone!”

Jaswanti, five years old, was left orphaned in the tribal attack on the city of Muzaffarabad in Kashmir on 22 October 1947. A well-meaning local Muslim adopted Jaswanti, renaming her Noori. Years later, in 1999, Noori reconnected with her family who had migrated to India after the partition of the subcontinent.

She remained Noori in Pakistan and was called Jaswanti in India!

As a tribute, honouring her wish, I now share a picture of my first meeting with her at Rawalpindi in 2014.

May Allah & Waheguru bless us all with the most profound lesson from Noori’s life – the acceptance of ‘Divine Will’.